The Skin I Live and (Virtually) Play In

Table of Contents

Introduction

Although I didn’t play as many video games as my peers as a child, the birth of my little sister at the age of 10 spurred a new love of play. As she grew older, we played a lot of video games together (especially Just Dance), and my family even purchased our first real console — a Wii mini. As the years went by and I went through high school and university, I had less time to play with my sister, but the video game bug stuck with her. One of her absolute favourite video games is The Sims. Through her gameplay and discussions about the game, I have learned a lot about custom content and mods. During one of these discussions, she mentioned a reoccurring issue within The Sims: the ashiness of the darker skin tones. Unsurprisingly, “seeing yourself in the games you play is important” (Richardson 2015) – especially in one that simulates real life.

This issue was brought to my radar once again when I watched a video by YouTuber As Told By Kenya (2020a) titled “The Sims 4 don't care about black people”, where she talks about how poorly darker skin tones are represented in the game: patchy, greyish, and lacking in vibrance — an issue, she says, that EA games has been slow to address for years:

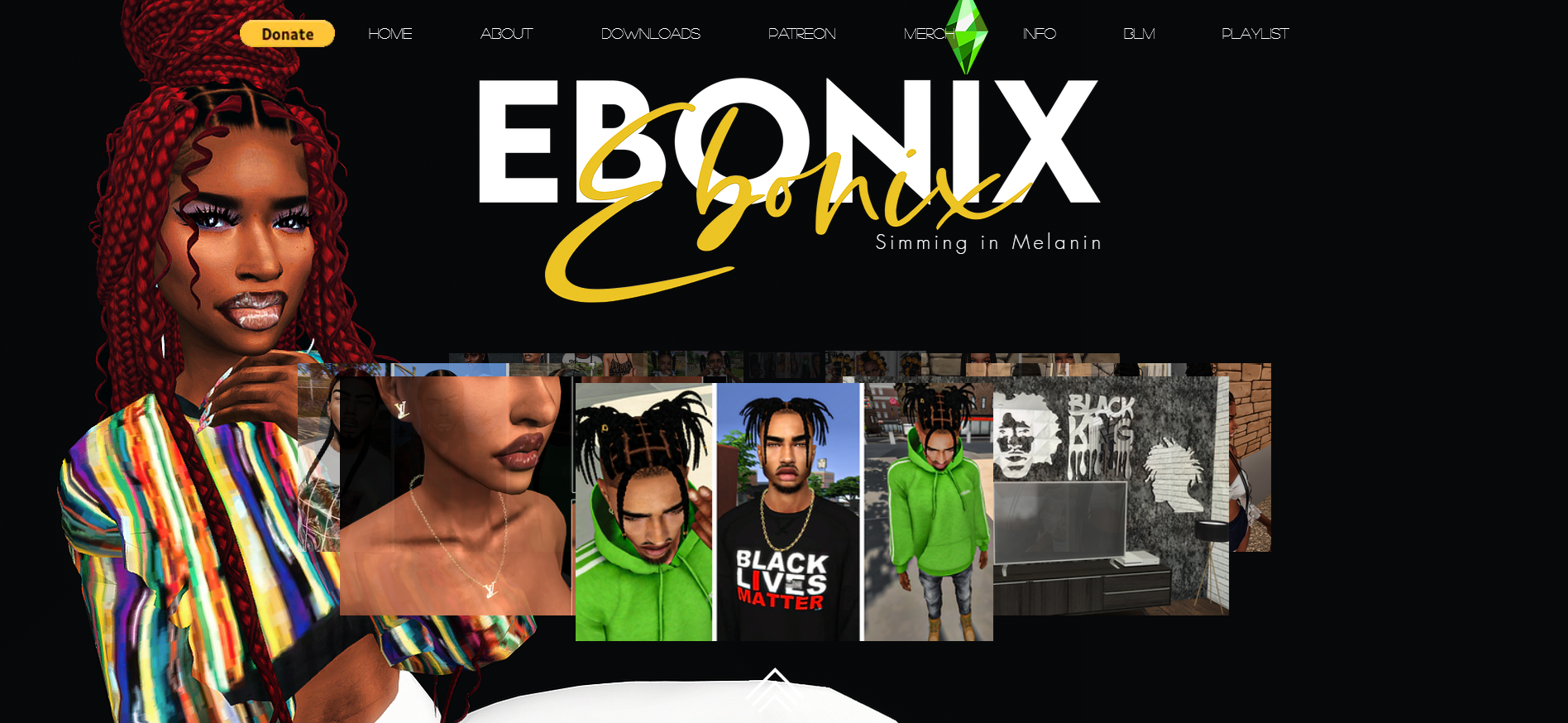

As I’ve learned in Virgil’s (2020) chapter in Black Futures, a number of Black modders such as Xmiramira, EbonixSims, MiaZaff1, and RaonyPhillips have taken it upon themselves to create better custom content for Simmers of colour. The caveat with this DIY approach, however, is that official expansion packs may cause custom content to malfunction. Moreover, the issue of ill-designed virtual characters of darker hues isn’t limited to The Sims.

This essay will look at the implications of having to write/design yourself into virtual spaces that didn't originally have you in mind, and how this falls into a larger pattern of such action in other spheres.

Games, Dialog, Politics, and Cultural Foundations

As Professor Westecott aptly writes in the notes posted on Canvas for Lecture 1:

Games can be regarded as dynamic systems that build an ongoing dialogue between the game designer and the game player within the context of the game experience. (p. 2-3 of the PDF)

When thinking of video games where Black and darker-skinned characters are not well represented: what kind of dialogue are game developers having with their Black players? It is clear from As Told By Kenya’s (2020b) later videos on The Sims, that although she is a big fan of the franchise, the continued excuses by EA have left a bad taste in the mouth of many game players.

When we consider that, as a representational form, “games are always already political […] as every artefact made by human hand expresses the values of its maker” (Westecott 2020, 23–24), one can understand how Kenya and other Sims player feel, as her video title stated, that The Sims creators do not value the representation of darker skin tones. Imbued within a larger society where structural inequalities exist, it comes as no surprise that game technology, as Cole and Depass (2017) argue, “is inextricable from its cultural foundations”. These cultural foundations affect not just video games, but the healthcare industry as well. Malone Mukwende, a medical student at St George’s, University of London, created a handbook called Mind the Gap to diagnose clinical signs in black and brown skin, because med students “are often not taught how to identify signs and symptoms in darker skin”, which can lead to misdiagnosis (CBC Radio 2020).

Beyond skin tone, many of our systemic issues are further accented in the mainstream video gaming industry. Certain games, in particular, have the unfortunate but warranted reputation of being spaces where hateful speech rooted in racism, sexism, homophobia, and so forth, thrive — so much so that a tweet that called the n-word a “gamer” word went viral (Hernandez 2019). As a child, the toxicity of multiplayer games such as Call of Duty was palpable to me, even as someone who didn’t own a console at the time. Even as an adult, I have heard that being called the n-word is to be expected in particular servers of certain games. Players can also become the target of hate speech based on the character they embody online. In articles for I Need Diverse Games and The Verge, Tauriq (2019) and Hernandez (2019) detail how players in Red Dead Online (RD:O) who play as Black characters “find themselves the frequent target of racial slurs”, “being called the n-word by players controlling white characters”, and “being hunted down for the crime of having dark skin” as racism specific to the era become “a part of the experience”.

Dark Skin Tone Representation in Gaming – Challenges

Now that I’ve addressed the obvious displays of racism in mainstream gaming culture, let’s circle back to the skin tone matter because, as Cole and DePass (2017) aptly put it, it is still rare to find video games “which explicitly feature protagonists of color”, as these main characters tend to be “a homogeneously white bunch”. Indeed, even as some games try to step outside of the white male canon, their characters still default to white – a point Jackson (2015) illustrates with Call of Duty III Black Ops, wherein character customization options for gender are provided (albeit, binary), but there are none for skin tones.

In the article “Black Skin Is Still A Radical Concept in Video Games”, the authors detail a number of issues that explain why dark skin in video games appears “drab, muddy and devoid of detail” : limited colour spectrums, bad lighting, 3D modelling bias, and colourism (Cole and DePass 2017). The first issue of limited palettes was present in the Nintendo Entertainment System, as highlighted by developer David D'Angelo: “The darker spectrum of color is very underrepresented, and there aren't many shades that work for displaying a character with a darker skin tone” (Cole and DePass 2017). The second issue, lighting, is due to the “baked” in nature of lighting in games. Because lighting is expensive to render, developers, as Cole and DePass (2017) explain, rely on game maps to determine how models in a scene will look. This technique, however, worsens inconsistencies in character lighting". In games like Skyrim, for instance, the darker-skinned character appears to have “the same dark, umber hue despite being in different environments”, unlike her lighter counterparts (Cole and DePass 2017). The third issue, bias, is explained by professor and game designer Robert Yang in Cole and DePass’s (2017) article:

‘When 3D artists test their new skin shaders, they often use a 3D head scan of a white guy named Lee Perry-Smith,’ he notes. ‘What does it mean if we're all judging the quality of our skin shader solutions by seeing who can make the best rendered white guy?’

The last issue Cole and DePass (2017) mention is colourism. In the video gaming context, this means that developers are more likely to design characters who are lighter “because people have an easier time identifying with them”. As Breakup Squad developer Catt Small is quoted as saying in the article, many developers “like to use the excuse that 'Oh, we wouldn't know how to light this person if we didn't make them lighter skinned” (Cole and DePass 2017).

Conclusion

Black Creators Picking Up the Slack

As we can see in this paper, diversity in gaming isn’t just a matter of slapping on a darker shade of beige on a character and calling it a day. Indeed, DePass (2016) tells us how:

Diversity in games also means doing the work to have a better end product. Don’t throw a character into a setting, make them black or brown with a palette swap and consider things done. Does having a protagonist of color mean your narrative changes? Does the world treat them differently? This will vary from game to game obviously, but having a colour blind game world isn’t a step towards progress either.

As mentioned in the introduction, many independent Black creators and game designers have found themselves taking on “the work that their white colleagues neglect” and “forging their own path forward when it comes to depicting black characters of all shades” (Cole and DePass 2017). Cole and DePass (2017) offer a few examples of indie games that represent darker skin especially well:

- The artwork for Card Witch by natasha d.j.excelsia

- Treachery in Beatdown City by NuChallenger and HurakanWorks

- Aurion: Legacy of the Kori-Odan by Kiroo Games

Whose Duty is it Anyway?

As excited as I was to play these game titles after learning about them in Cole and DePass’s article, I wondered whether the onus and burden of representation should be on Black and other racialized creators. Shawn Alexander Allen, one of the developers behind Treachery in Beatdown City, stated in Cole and DePass’s (2017) article that, "People that are not black don't think about the different shades of blackness or browness. (…) That's a problem.”

Thinking of this issue brought to mind the virtual talk that happened OCAD a few weeks ago. During the Q&A period, one of our classmates asked the keynote speaker whether she had plans to expand the body diversity of her characters. Unfortunately, the recording of the meeting is no longer available, so I cannot provide a direct quote, but I remember that the speaker responded that although she believes in inclusivity of all body types, she is primarily focusing on Indigenous representation. I reckon that my initial, knee-jerk reaction was to think that the response was a bit of a cop-out, but I took some time to reflect on this.

I realized that although representation on many, intersecting fronts is important (in fact, the speaker later presented mockups for new characters with different body shapes), we shouldn’t place all of these expectations on independent developers and designers from marginalized and underrepresented communities. It is a lot to ask these creators to pick up all the slack that the wider, mainstream gaming industry is not properly addressing. Many of the Black Sims modders, I’ve noticed, give their custom content away for free or through inexpensive Patreon pledges — all of this for a franchise that surpassed $5 billion US dollars in lifetime sales in 2019 (Valentine 2019). This highlights the need for more creators, developers, and designers from different backgrounds. Bringing diverse creators into the fold, however, presents its own set of challenges and barriers which, along with the unhealthy work culture in the gaming industry, could be an entire essay in itself.

Final Thoughts

To wrap up, I cannot begin to express how grateful I am for the work that Tanya DePass and others are doing in this area, and this paper wouldn’t be possible without the writings published on I Need Diverse Games. As Cole and DePass (2017) aptly put it, “ten years ago, we wouldn't be having this conversation because there wouldn't be characters to have this conversation about.” This, I believe, is a testament to how far things have come in the sphere of gaming. This course, in particular, has expanded my views on gaming, play, and players, and has challenged many of my attitudes on the matter. Although mainstream video games seem to be the most visible (likely because of funding), I’ve been encouraged by this class to seek out and support expanded and experimental games and game modders.

Tanya DePass (2016) says it best: “We’re simply tired of the same old, same old. Gamers want new stories, new landscapes to play in.” And, lest we forget, better skin tone choices!

References

As Told By Kenya. 2020a. The Sims 4 Don’t Care about Black People. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D4qKzWToYF4.

———. 2020b. The Sims 4 Got New Skintones....but We Still Not Friends. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=22WnEchdHS0.

CBC Radio. 2020. ‘Medical Student Creates Handbook for Diagnosing Conditions in Black and Brown Skin | CBC Radio’. CBC Radio, 21 July 2020. https://www.cbc.ca/radio/asithappens/as-it-happens-tuesday-edition-1.5657448/medical-student-creates-handbook-for-diagnosing-conditions-in-black-and-brown-skin-1.5657451.

Cole, Yussef, and Tanya DePass. 2017. ‘Black Skin Is Still A Radical Concept in Video Games’. Waypoint Games by VICE. 1 March 2017. https://www.vice.com/en/article/78qpxd/black-skin-is-still-a-radical-concept-in-video-games.

DePass, Tanya. 2016. ‘Let’s Talk about What Diversity Actually Means’. I Need Diverse Games (blog). 4 April 2016. https://ineeddiversegames.org/2016/04/04/lets-talk-about-what-diversity-actually-means/.

Hernandez, Patricia. 2019. ‘Playing Red Dead Online as a Black Character Means Enduring Racist Garbage’. The Verge. 15 January 2019. https://www.theverge.com/2019/1/15/18183843/red-dead-online-black-character-racism.

Jackson, Shareef. 2015. #GamingLooksGood #18: Black Ops III Campaign Fail. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8Cuqx_M9SiU&t=124s.

Richardson, Sarah. 2015. ‘Diversify Tabletop: Finding Diverse Designers Among the D20s’. I Need Diverse Games (blog). 13 November 2015. https://ineeddiversegames.org/2015/11/13/diversify-tabletop-finding-diverse-designers-among-the-d20s/.

Tauriq. 2019. ‘On Red Dead Redemption and Historical Accuracy’. I Need Diverse Games (blog). 17 January 2019. https://ineeddiversegames.org/2019/01/17/on-red-dead-redemption-and-historical-accuracy/.

Valentine, Rebekah. 2019. ‘The Sims Franchise Surpasses $5b in Lifetime Sales’. GamesIndustry.Biz. 29 October 2019. https://www.gamesindustry.biz/articles/2019-10-29-the-sims-franchise-surpasses-usd5b-in-lifetime-sales.

Virgil, Amira. 2020. ‘The Black Simmer’. In Black Futures, edited by Kimberly Drew and Jenna Wortham, First edition, 82–85. New York: One World. https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/553674/black-futures-by-edited-by-kimberly-drew--jenna-wortham/.

Westecott, Emma. 2020. ‘Game Sketching: Exploring Approaches to Research-Creation for Games’. Virtual Creativity 10 (1): 11–26. https://doi.org/10.1386/vcr_00014_1.