Online Natural Hair Groups as Sites of Afro Cyber Resistance | Digital Theory Paper

Abstract

Hair and hair texture remain important identifiers and signifiers of culture and ethnicity. The subject of natural hair is a topical issue; although recent laws have been passed across North America to ban discrimination against afro-textured hair, it is still an ongoing issue in professional and interpersonal domains. Online natural hair groups, like other spaces for racialized and marginalized people, are a space for support, self-determination, and self-definition (Williams 2016) that surpass the limitations of the physical. Indeed, these online communities are important sites of Afro Cyber Resistance, a term coined by contemporary artist Tabita Rezaire. Existing within racialized and gendered virtual spaces where hegemonic representation is contested, these communities encourage Black participants to transition to and retain their natural afro-textured hair—an enduring symbol of resistance.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Overview

Hair and hair texture remain important identifiers and signifiers of culture and ethnicity (Ellington 2015). For Black women and people, in particular, the subject of natural hair is a contentious and topical issue. Although recent laws have been passed across North America to ban discrimination against afro-textured hair, it is still an ongoing issue in professional and interpersonal domains (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 - A collection of news headlines covering incidents of hair discrimination in Canada, the United States, and South Africa (collage made by Candide Uyanze)

In addition to this hostility, finding high-quality and affordable salons that cater to natural afro-textured hair can prove challenging. Amid these challenges, many people of African descent find refuge in online natural hair groups. Like other spaces for racialized and marginalized people, online natural hair communities are important spaces for support, self-determination, and self-definition (Williams 2016) that surpass the limitations of the physical. In fact, Black women and people looking for advice on their natural hair are more likely to visit one of the “more than 133 million ‘natural hair blogs’ that emerge through a Google search than to visit a local salon” (Gill 2015, 72). Indeed, in a survey conducted by the natural hair website Black Girl with Long Hair, only 6% of the 2,300 participants answered that they visited natural hair stylists regularly as opposed to going the DIY (do-it-yourself) route (Gill 2015, 73).

Defining “Natural Hair”

When speaking of “natural hair” in this paper, I am referring to the hair of people of African descent which is free from straightening agents (such as relaxers) or the use of damaging heat which alters the texture of the hair (Gill 2015, 70; Williams 2016, 8). Natural hair is characteristically coily, curly, or wavy and tends to grow up and away from the scalp (Ndichu and Upadhyaya 2019, 45; Williams 2016, 8). According to a Mintel study cited in Gill (2015), 70% of African-American women say they wear or have worn their natural hair (without relaxers) (72) – a rate that has not always been so high.

Natural Hair History

In the 15th century, natural hair hairstyles in West African societies were used to communicate messages and interact with society. Indeed, different ornaments and styles symbolized different types of identities such as age, engagement, marriage, wealth, rank in society, and so on (Marco 2012, 13; Ndichu and Upadhyaya 2019, 47). The relationship between African peoples and our hair, however, was drastically altered at the dawn of the transatlantic slave trade (Marco 2012, 14). For centuries, colonialism and slavery dominated Black culture and introduced into the diaspora a racial hierarchy that elevated European attributes to the detriment of African features (Marco 2012, 17). This system was not only critical but also harmful in manipulating the perceptions and ideals of beauty for people of African descent, with hair being a central element (Marco 2012, 14).

Although beauty ideals change over time and from culture to culture, the promotion of Western standards of beauty has persisted into the post-colonial era. The ideal of having long, smooth, and straight hair has been assimilated by people of many races (Ndichu and Upadhyaya 2019, 48–49). These ideals, which are disseminated and perpetuated in media images, are internalized from an early age. As opposed to straight hair, Black natural hairstyles such as afros, locs, braids, and twists are perceived as being unconventional, unprofessional, uncivilized, unkempt, unfeminine, and unattractive—attitudes and prejudices that have their roots in depictions of Africa and her descendants by Enlightenment thinkers and early American settlers (Omotoso 2018, 6; Ndichu and Upadhyaya 2019, 49; Williams 2016, 6–9; King 2017).

In this process, an unconscious burden is placed on Black people, who may feel the need to wear unnatural hairstyles and/or apply chemicals to gain social acceptance in school, work, and other normative social settings (Omotoso 2018, 6, 13; Ndichu and Upadhyaya 2019, 49). This need is further accented by the politicization and discrimination of afro-textured natural hair. A study led by King revealed thirty cases of discrimination against Black girls and young women with natural hairstyles in American primary and secondary schools, as reported in the media from 2007 to 2017 (2017). As Omotoso (2018) notes, this marginalization contributes to low self-esteem and self-hatred (13).

Because of the structure and biological characteristics of natural hair, people of African descent must artificially alter their hair to have straight hair that falls (Ndichu and Upadhyaya 2019, 49). This is achieved temporarily using heated styling tools such as hot combs, hairdryers, and flat irons, or permanently with chemical hair relaxers, which permanently alter the structure of the hair shaft (Ndichu and Upadhyaya 2019, 49). In the Black community, hair straightening has become so prevalent and commonplace that by adolescence, many girls have already had their hair relaxed (Williams 2016, 11). In Kenya, chemical straighteners accounted for 43% of sales of hair care products in 2014 (Ndichu and Upadhyaya 2019, 51). This radical change in texture, however, poses dangers to the health of the hair and body. Incorrect or excessive use of heat can cause a permanent change in the hair texture (Williams 2016, 11), which may lead to breakage. Chemical relaxers can cause hair loss, allergic reactions, scalp burns, and weakening of the hair, (Ndichu and Upadhyaya 2019, 49). According to a study published in the American Journal of Epidemiology and cited in a legal enforcement by the City of New York, the risk of developing uterine leiomyomata in African-American women increases as the duration and frequency of chemical relaxer use increases (Wise et al. 2012; City of New York 2019).

Given these adverse health effects, in the early 2000s, many Black women decided to abandon hair relaxers, either by cutting off the damaged hair (colloquially known as the "big chop") or by ceasing the straightening to transition to their natural hair (Williams 2016, 5). Thus, the natural hair movement was born. Williams (2016) defines this transition as a physical, mental, emotional, and often spiritual process where women of African descent are invited to accept their natural hair texture (1). According to Gill (2015), in the United States, the use of chemical hair straighteners, which were the main expense for Black women's hair in the second half of the 20th century, is steadily declining; indeed, the sector has registered a decrease of 26% since 2011 (72).

To facilitate this transition, virtual communities for natural hair have formed, consisting of websites, forums, blogs, Instagram profiles, YouTube channels, Facebook groups, and so forth dedicated to sharing information on the care of the natural, Afro-textured hair of Black women (Williams 2016, 1). According to Williams (2016), these spaces of "self-definition and self-determination" (107) often coincide with the first experience of having natural hair for numerous women, since many began to get relaxers from a very young age, and have no memories or previous experience with their real hair (11). Aside from going natural, online natural hair communities encourage Black women to start changing their attitudes, thoughts, and feelings about their hair (Williams 2016, 11). This resistance to hegemony brings to mind the liberation movements of the Black Panthers in the 1960s in the United States and the Soweto Uprising of the 70s in South Africa – in both cases, the Afro was a symbol of freedom and rejection of the status quo (Marco 2012, 18).

Rezaire’s Afro Cyber Resistance

The rejection of the status quo in the South African context is a concept that is also explored in Tabita Rezaire’s paper “Afro Cyber Resistance: South African Internet Art”. Instead of hair, Rezaire (2014) delves into – as the title implies – Internet art practices in South Africa as “a manifestation of cultural dissent towards western hegemony online” (185), using VIRUS SS 16, Video Party 4 (VP4), and the WikiAfrica project as case studies. The term she uses, “Afro Cyber Resistance”, denotes a visual and cultural gesture that contests the online representation of African cultures and bodies. The text highlights the Internet’s crucial role in challenging and raising awareness of African misrepresentation and stereotypes.

Thesis

The present paper will expand Tabita Rezaire’s notion of « Afro Cyber Resistance » to include online natural hair groups. Indeed, this paper will argue that virtual natural hair communities are important sites of Afro Cyber Resistance, wherein they contest Western hegemony online, challenge the online representation of Black bodies and cultures, and surpass the limitations of the physical.

Racial Space, Social Media, and Natural Hair Groups

When considering the larger ecosystem that natural hair blogs, websites, and social media accounts exist in, I’m reminded of Benjamin Bratton’s (2015b) concept of the Stack: the assemblage of various planetary-scale technologies that form a bigger, coherent whole as opposed to unrelated and isolated types of computation. As Bratton (2015a) explains, the Stack acts as a political machine and model that divides the world into sovereign spaces. As Terranova (2004) states, the political dimensions of culture, thus far, have been “conceived mainly in terms of resistance to dominant meanings” (8). Bringing to mind Stuart Hall’s (2006) theories on encoding and decoding, Terranova (2004) continues by stating that, “the set of tactics opened up have been those related to the field of representation and identity/difference (oppositional decodings; alternative media; multiple identities; new modes of representation)” (8-9).

There’s a cultural struggle waged in this representational space, as Terranova (2004) argues (37). The reorientation of forms of power and modes of resistance can notably be seen on social media – one of the primary domains for natural hair groups.

Counter-Hegemony on Social Media

As Bouvier explains, social media is not just used to maintain social relationships, but also in identity construction and engagement with socially relevant issues (Bouvier 2015, 151). One would simply have to think of the global resurgence of the #BlackLivesMatter movement during the summer of 2020 to understand the latter point. In their study, Bonilla and Rosa (2015) considered the use of hashtags in social movements and reflected on how social media channels have become influential in challenging and authenticating occurrences of state-sanctioned violence and the distortion of Black bodies in the media, citing the footage of the police’s use of a chokehold in Eric Garner’s murder which was circulated on social media.

Wessinger et al. (2017) remark how despite making up 13% of the U.S. population, African-Americans comprised 18% of Twitter users (173). This overrepresentation allows them to reappropriate these tools to control their narratives and create a space for Black people in the States and around the world to express individual opposition and dissent against collective abuse, misrepresentation of Black bodies in the media, and excessive police violence (Bonilla and Rosa 2015, 5; Weissinger, Mack, and Watson 2017, 173–74). This phenomenon resembles what Bouvier described in their paper, wherein globalization leads not to a “global village”, but, rather, an intricate network of parts interconnected to different degrees and in different ways (Bouvier 2015, 150). It also brings to mind Galloway & Thacker’s take on the protocological and counterprotocological nature of networks, and their power to transform the concept of political resistance (Galloway and Thacker 2004, 23).

Being Black Online: Space, Race, and Racial Space

Exploring the mobilization of these networks by Black users allows me to ponder further on the space that we occupy. When talking about space, here, I refer to the concept detailed in Hoops’s (2014) text:

Space refers to the physical, geographical contours of sites, the ideological signification of those material dimensions, and the movement of people in those locations. Space theoretically matters because it structures life on both lived and discursive levels (McKerrow, 1999). Space is not confined to physical location, but imbued with meaning through representation. (195)

Terranova (2004) provides additional context on information flows within space, wherein:

Space becomes informational not so much when it is computed by a machine, but when it presents an excess of sensory data, a radical indeterminacy in our knowledge, and a nonlinear temporality involving a multiplicity of mutating variables and different intersecting levels of observation and interaction. (37)

Indeed, the movement of people and information in space is essential, but not all interactions are made equal. Space, as Green & Singleton (2006) posit, is racialized, sexualized, gendered, and classed. Indeed, they explain that the "ease of access and movement through space for different groups is subject to constant negotiation and contestation, and is embedded in relations of power" (Green and Singleton 2006, 859).

The role of space in constructing racial difference and reinforcing colorblindness ideology

These power relations, however, are often obfuscated to characterize spaces – both online and off – as “colour-blind” and “egalitarian”. As Bratton (2015a) aptly surmises, “it is far less important how the machine represents a politics than how ‘politics’ physically is that machinic system” (44). Imbued within a larger society of systemic oppression, the “machines” that occupy and surround our spaces embody these politics.

In their study of a rural American town comprised of white and Hispanic residents, Hoops (2014) discusses how the social production of space conceals inequality by reinforcing colorblindness, while also rendering whiteness visible to satisfy certain identity needs (such as affirmation) (210). Hoops (2014) notes how immigrant and white people living in the farm communities tended to downplay ethnic differences in favour of colorblindness, despite residing in very different social spaces with their own cultural and symbolic boundaries (196). In the study, the "white areas" of the town were simply known by their location, while the Hispanic areas of town were dubbed "Tortilla Flats" by the residents (Hoops 2014, 200). In the same way, "Black Twitter" has entered the everyday netizen's vernacular, while "White Twitter" (or “Cisgender Twitter” or “Heterosexual Twitter” and so forth) almost sounds silly. Though the Internet may not be an explicitly "white" space, numerous factors have contributed to digital inequalities: real-life hierarchies and power relations are reproduced, and racism is amplified (Matamoros-Fernández 2017, 933). Twitter has even been described as an outlet where harassment and hate speech (including sexism and racism) thrive (Matamoros-Fernández 2017, 933).

Bhabha (2004) cautions against universalizing "the spatial fantasy of modern cultural communities as living their history 'contemporaneously,' in a 'homogeneous empty time' of the People-as-One," arguing that this denies minorities of liminal, marginal spaces where they can intervene and rearticulate totalizing myths of the nation's culture (358). Hoops (2014) mirrors this sentiment by explaining that:

As racial actors, we orient ourselves in reference to our perceptions of space and subsequently make decisions about our behavior in those locations; for example, if we find a space affirming or threatening, that perception will influence whether we enter or avoid that site. (195-96)

As public spaces in Western societies have often been dominated by cisgender, heterosexual, white men and their use of violence or “aggressive gaze”, other groups have had to fight for "their own spatial positioning" (Green and Singleton 2006, 859). In a similar vein, some spaces can be perceived as being more welcoming/safe when their occupants have similar identities, especially when other spaces become no-go zones "on the grounds of 'race'" (Green and Singleton 2006, 859).

Navigating space as racialized actors: Theory of Racial Space

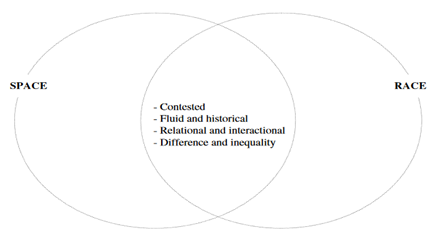

The concept of race and space intersecting is pushed further by a theory on the synergy of "racial space" by Neely & Samura (2011) (see Figure 2). The theory of Racial Space provides four characteristics of space that intersect with existing theories on racialization and race: it is contested, fluid and historical, interactional and relational, and defined by inequality and difference (Neely and Samura 2011, 1934).

While reflecting on Blackness in cyberspace, Rubin (2016) argues the following:

Blackness as an identity has never been fixed to place but rather finds itself articulated through space and, more importantly, time. Movement has defined black identity and served as an origin in and of itself. (74)

At the same time, technological innovation has provided the Black community with the necessary conduit to communicate its fluidity, defying archaic binaries (Rubin 2016, 74, 77). This allows, for instance, Black people who participate in online natural hair groups to communicate the multiplicities of our hairs, body extensions, and personas. This is why, as Terranova (2004), posits, the cultural politics of information sidesteps the relationship between what’s possible and what’s real to reveal the connection between the virtual and the real, going “beyond the metaphysics of truth and appearance of the utopian imagination informing the revolutionary ideals of modernity” (26). The virtual thus appears as a space where the openness of socio-cultural and biophysical processes leads to the eruption of the inventive and the improbable (Terranova 2004, 27). As such, communication is not limited to being a site where culture is reproduced, but also an indefinite production that crosses the social and represents an informational milieu that reveals the transformational potential of the political (Terranova 2004, 9).

Online Natural Hair Groups

Online natural hair groups are, certainly, spaces where community is cultivated, contested, and defined in the world of digital beauty (Gill 2015, 71–72).

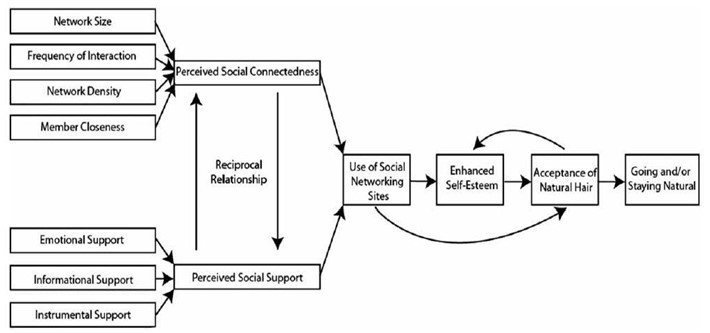

Accepting natural hair through social media: Ellington Model

In one of the few peer-reviewed studies centred around the use of digital platforms for natural hair, Tameka N. Ellington devises a model on the influence of social networks in the acceptance of natural hair (2015) (see Figure 3). Adapted from the Standpoint Theory (ST) model by Goswami et al. and Asante's Afrocentric Theory (AT) perspective, the model demonstrates that network size, network density, and frequency of interactions influence the Perceived Social Connectedness. It also indicates that emotional, informational, and instrumental support have an impact on the Perceived Social Support. Together, Perceived Social Connectedness and Perceived Social Support influence the use of social networking, self-esteem, acceptance of natural hair, and the decision to stay natural.

Figure 3 - Ellington's (2015) model for the influence of social media networks on the acceptance of natural hair

As Bratton (2015a) surmises:

Platforms are generative mechanisms — engines that set the terms of participation according to fixed protocols (e.g., technical, discursive, formal protocols). They gain size and strength by mediating unplanned and perhaps even unplannable interactions. (45)

Natural hair groups have, certainly, been sites for unplanned interactions that go beyond their initial purpose.

Online natural hair groups as the new salons

Gill (2015) notes that members of these online spaces can find information and education that have little to do with hair (74). On the website Napturality, forum topics exist on parenting, life management, entrepreneurship, fashion, health and wellness, spirituality, home and gardening, travel, and even an online book club (Gill 2015, 74). As a longtime participant of natural hair groups on social media, I have witnessed this shift from hair advice to a general discussion board. As Gill (2015) further explains:

[B]lack women with natural hair are not only abandoning beauty shops because of cost, or because they can learn how to care for their hair online, but because these digital spaces can often replicate the information sharing and exchange of advice that are so crucial to black women’s lives. (74-75)

Although salons remain important gathering spaces for Black women and people around beauty and adornment practices, technology has extended and created new spaces to debate, educate, and style afro-textured hair (Gill 2015, 72). These digital venues are also crucial for those of African descent who do not have access to salons and products that cater to natural hair, as they are most often found in larger metropolitan areas with a significant Black population. Even in cities like New York City, Black women often have trouble finding affordable, high-quality hairstylists for their natural hair (Gill 2015, 72–73). In Canada, public colleges and cosmetology schools provide inadequate training for afro-textured hair, making salons catered to non-Black clients a non-option. Many of the natural hair stylists I have spoken to in Ottawa and Montréal had to receive their training in the United States.

Gill (2015) discusses the parallels between brick and mortar beauty salons and online natural hair groups, noting how in beauty salons, customers navigate a private grooming experience within a shared public space (72). Aside from the familiarity fostered between the client and beautician, individuals in the space may be strangers, but find common ground for discussion and debate (Gill 2015, 72).

Online natural hair groups as archives for Black women and people

In addition to extending physical spaces, natural hair groups remain, nonetheless, a massive, unique, and interactive archive of images and documents related to growing, styling, adorning, and caring for afro-textured hair (Gill 2015, 75; Williams 2016, 5). The highly visual nature of these digital spaces is demonstrated through the collection of these images under ubiquitous hashtags such as #TeamNatural and #NaturalHair on Pinterest, Tumblr, and Instagram (Gill 2015, 75). This gathering of similar ideas and thoughts across digital sites “provide unique insight into the complexities of community building around a supposedly common aesthetic” (Gill 2015, 75).

This vast collection of user-generated data brings to mind Moravec’s proposal to download human consciousness into a computer so that machines can become “the repository of human consciousness”, as cited in Hayles (1999, xii). This can also be likened to Rezaire’s (2017) video artwork PREMIUM CONNECT, where one of the audio snippets describes communicating with our ancestors as a “divine record of consciousness” or “divine Internet” which allows us to draw on the collective minds (“computers”) and lifetimes of the ones who came before us (06:41-07:36).

The importance of this online archive of affirming imagery is further stressed by Gill (2015), who maintains that:

More than just a narcissistic display of self-indulgence, the assemblage of images collected under #TeamNatural provides a space to challenge what Kobena Mercer calls the “ideologies of the beautiful,” which have served to relegate black women, particularly those with Africanized features, outside its norms. (76)

Gill (2015) further discusses how these selfies by Black, natural-haired women and people are a way to assert ourselves and create alternative narratives of beauty (76). This distinction can be likened to what Hayles (1999) describes as “distinguishing between the enacted body, present in the flesh on one side of the computer screen, and the represented body, produced through verbal and semiotic markers constituting it in an electronic environment” (xiii). After all, tagging a selfie to these hashtags and adding it to the repository links our personal quest for affirmation to a larger community (Gill 2015, 76).

Conclusion

Recapitulation

To conclude, online natural hair groups, which emerged at the dawn of the natural hair movement, are important spaces of “Afro Cyber Resistance”. This concept, coined by Tabita Rezaire (2014), denotes a visual and cultural gesture that contests the representations of African cultures and bodies online, challenging Western hegemonic misrepresentations and stereotypes of African people.

Natural hair communities, which are comprised of websites, forums, blogs, Instagram profiles, YouTube channels, Facebook groups, etc., exist in the virtual space known as The Stack, as termed by Bratton (2015b). As Green & Singleton (2006) explain, spaces are gendered and racialized, wherein actors, personas, avatars fight to establish spatial positioning. In these natural hair groups, users dissent hegemonic representations of beauty, acting within the larger cultural struggle waged within representational space.

These communities encourage Black participants to transition and retain their natural hair — a symbol of resistance — as Ellington’s (2015) model and study demonstrate. They act both as interactive and digital archives of the represented Black body — repositories of the Black consciousness, to borrow from Hayles (1999) — and as neo-salons which provide information as a reorientation of resistance and power, as Gill (2015) illustrates. As such, Afro Cyber Resistance can take the form of South African internet art, as Rezaire (2014) posits, as selfies tagged under #NaturalHair, or as a discussion thread on politics in a natural hair Facebook group.

Caveats

As Matamoros-Fernández (2017) noted, real-life hierarchies, power relations, and inequalities are reproduced, amplified, and thrive (933). As such, natural hair groups are not exempt from some of the challenges faced in other spaces for marginalized people.

Firstly, in a thread titled “There is No Such Thing as Black Space....” on Lipstick Alley (the self-described largest African-American forum on the Internet), user “froggyluv2” (2013) lamented at the continued encroachment, co-opting, censoring, tone-policing, discrediting, reprimanding, and patronizing by non-Black commentators in online spaces that Black people carve for themselves, recalling antebellum slave codes. Although an anonymous post, it is important to note some of the challenges and grievances expressed by Black users online, dispelling the oft-alluded utopic notion of a “safe (digital) space” for Black people. In terms of natural hair groups, Gill (2015) cautions that:

[T]he TeamNatural hashtag and the community that has developed online around it have also served to restrict conversation and place black women’s bodies once again at the center of contentious debates around politics and identity. Much of the conflict has come around the word natural, often wielded as a self-righteous sword among black women. (76)

As Galloway & Thacker (2004) note, “the protocological nature of networks is as much about the maintenance of the status quo as it is about the disturbance of the network” (23-24).

Secondly, although dedicated natural hair websites and blogs exist, many of these communities and archives live on social media sites or third-party platforms such as Pinterest and tumblr. As Bouvier (2015) states, social media sites are driven by the pursuit of profit, powered by the computationally-assisted collection of consumer preferences, patterns, and past behaviour (153). Cultural and personal tastes are identified, used, and fed back to individuals and sub-individuals in the form of advertisements, promotions, and connections with other groups and people (Bouvier 2015, 153; Terranova 2004, 34). As Terranova (2004) notes, the rise of information as a concept led to the novel collection and storing techniques which have “simultaneously attacked and reinforced the macroscopic moulds of identity (the gender, race, class, nationality and sexuality axes)” (34). The author supports this argument by stating the following:

These patterns identified by marketing models correspond to a process whereby the postmodern segmentation of the mass audiences is pursued to the point where it becomes a mobile, multiple and discontinuous microsegmentation. It is not simply a matter of catering for the youth or for migrants or for wealthy entrepreneurs, but also that of disintegrating, so to speak, such youth/migrants/entrepreneurs into their microstatistical composition – aggregating and disaggregating them on the basis of ever-changing informational flows about their specific tastes and interests. (Terranova 2004, 34–35)

Although many were drawn to online natural hair groups because of the high cost of natural hair salons, this does not necessarily make natural hair a more affordable enterprise — in fact, the digital space is facilitating an increase in sales (Gill 2015, 73–74). Many of these advertisers prey on existing insecurities of having longer, looser-textured, and more “manageable” hair, leading to a phenomenon known in natural hair communities as “product junky-ism”. Additionally, fostering community in a space that, at its core, is not designed for such purpose means that we are vulnerable to the whims, mergers, and closures of tech giants. Alternative, self-hosted, and (potentially) open-source platforms should be considered to preserve this growing archive (albeit challenging, considering the multiplicity and sheer volume of communities and data).

Opening

As I have described it, information is neither simply a physical domain nor a social construction, nor the content of a communication act, nor an immaterial entity set to take over the real, but a specific reorientation of forms of power and modes of resistance. On the one hand, it is about a resistance to informational forms of power as they involve techniques of manipulation and containment of the virtuality of the social; and on the other hand, it implies a collective engagement with the potential of such informational flows as they displace culture and help us to see it as the site of a reinvention of life. (Terranova 2004, 37)

Natural hair groups, as the “site of a reinvention of life”, present a fascinating study of the symbiosis between humans and electronic computers described in Licklider’s (1960) text. As we approach our post-pandemic realities, the blurring of boundaries between physical and digital spaces intensifies. As such, it is important to reflect on the future and health of natural hair communities as critical sites of Afro Cyber Resistance.

References

Bhabha, Homi K. 2004. The Location of Culture. Routledge Classics. London ; New York: Routledge.

Bonilla, Yarimar, and Jonathan Rosa. 2015. ‘#Ferguson: Digital Protest, Hashtag Ethnography, and the Racial Politics of Social Media in the United States’. American Ethnologist 42 (1): 4–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/amet.12112.

Bouvier, Gwen. 2015. ‘What Is a Discourse Approach to Twitter, Facebook, YouTube and Other Social Media: Connecting with Other Academic Fields?’ Journal of Multicultural Discourses 10 (2): 149–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/17447143.2015.1042381.

Bratton, Benjamin H. 2015a. ‘Platform and Stack, Model and Machine’. In The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty, 41–72. Software Studies. Cambridge: The MIT Press. https://direct-mit-edu.proxy.bib.uottawa.ca/books/book/3504/The-StackOn-Software-and-Sovereignty.

———. 2015b. ‘Preface’. In The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty, xvii–xx. Software Studies. Cambridge: The MIT Press. https://direct-mit-edu.proxy.bib.uottawa.ca/books/book/3504/The-StackOn-Software-and-Sovereignty.

City of New York. 2019. ‘Legal Enforcement Guidance on Race Discrimination on the Basis of Hair’. City of New York. 18 February 2019. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/cchr/law/hair-discrimination-legal-guidance.page.

Ellington, Tameka N. 2015. ‘Social Networking Sites: A Support System for African-American Women Wearing Natural Hair’. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education 8 (1): 21–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/17543266.2014.974689.

froggyluv2. 2013. ‘There Is No Such Thing as Black Space....’ Lipstick Alley. https://www.lipstickalley.com/threads/there-is-no-such-thing-as-black-space.875044/.

Galloway, Alexander, and Eugene Thacker. 2004. ‘Protocol, Control, and Networks’. Grey Room 17 (October): 6–29. https://doi.org/10.1162/1526381042464572.

Gill, Tiffany M. 2015. ‘#TeamNatural: Black Hair and the Politics of Community in Digital Media’. Journal Of Contemporary African Art 2015 (37): 70–79. https://doi.org/10.1215/10757163-3339739.

Green, Eileen, and Carrie Singleton. 2006. ‘Risky Bodies at Leisure: Young Women Negotiating Space and Place’. Sociology 40 (5): 853–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038506067510.

Hall, Stuart. 2006. ‘Encoding/Decoding’. In Media and Cultural Studies: KeyWorks, edited by Meenakshi Gigi Durham and Douglas Kellner, Rev. ed, 163–73. KeyWorks in Cultural Studies 2. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Hayles, N. Katherine. 1999. ‘Prologue’. In How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics, xi–xiv. ACLS Humanities E-Book. Chicago, Ill: University of Chicago Press.

Hoops, Joshua F. 2014. ‘Discourses of Affirmation in the Spatialization of Whiteness’. Journal of International and Intercultural Communication 7 (3): 193–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/17513057.2014.929200.

King, Vanessa. 2017. ‘Race, Stigma, and the Politics of Black Girls Hair’. M.S., United States -- Minnesota: Minnesota State University, Mankato. https://search.proquest.com/docview/2041049551/abstract/C83515A9527F4A9FPQ/1.

Licklider, Joseph CR. 1960. ‘Man-Computer Symbiosis’. IRE Transactions on Human Factors in Electronics 1 (HFE-1): 4–11.

Marco, Jenna-Lee. 2012. ‘Hair Representations among Black South African Women: Exploring Identity and Notions of Beauty’. M.A., South Africa -- Pretoria: University of South Africa.

Matamoros-Fernández, Ariadna. 2017. ‘Platformed Racism: The Mediation and Circulation of an Australian Race-Based Controversy on Twitter, Facebook and YouTube’. Information, Communication & Society 20 (6): 930–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1293130.

Ndichu, Edna G., and Shikha Upadhyaya. 2019. ‘“Going Natural”: Black Women’s Identity Project Shifts in Hair Care Practices’. Consumption Markets & Culture 22 (1): 44–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253866.2018.1456427.

Neely, Brooke, and Michelle Samura. 2011. ‘Social Geographies of Race: Connecting Race and Space’. Ethnic and Racial Studies 34 (11): 1933–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2011.559262.

Omotoso, Sharon Adetutu. 2018. ‘Gender and Hair Politics: An African Philosophical Analysis’. Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies 12 (8): 5–19.

Rezaire, Tabita. 2014. ‘Afro Cyber Resistance: South African Internet Art’. Technoetic Arts: A Journal of Speculative Research 12 (2): 185–96. https://doi.org/10.1386/tear.12.2-3.185_1.

———. 2017. PREMIUM CONNECT. HD Video. https://vimeo.com/247826259.

Rubin, Joel. 2016. ‘Hip Hop Videos and Black Identity in Virtual Space’. The Journal of Hip Hop Studies 3 (1): 74–85.

Terranova, Tiziana. 2004. ‘Three Propositions on Informational Cultures’. In Network Culture: Politics For the Information Age, 6–38. London, UNITED KINGDOM: Pluto Press. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/oculocad-ebooks/detail.action?docID=3386160.

Weissinger, Sandra Ellen, Dwayne A Mack, and Elwood Watson, eds. 2017. Violence against Black Bodies: An Intersectional Analysis of How Black Lives Continue to Matter. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Williams, Myrtie Rena. 2016. ‘Transition: Development of the Online Natural Hair Community and Black Women’s Emerging Identity Politics’. M.A., United States -- California: University of California, Davis. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1833195702/abstract/9A71FAAD7FA4467PQ/1.

Wise, L. A., J. R. Palmer, D. Reich, Y. C. Cozier, and L. Rosenberg. 2012. ‘Hair Relaxer Use and Risk of Uterine Leiomyomata in African-American Women’. American Journal of Epidemiology 175 (5): 432–40. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwr351.

Comments